| Ceratopsia Fossil range: Late Jurassic–Late Cretaceous | |

|---|---|

Triceratops skeleton at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. | |

| Scientific classification

| |

|

Ceratopsia Marsh, 1890 | |

| |

Ceratopsia or Ceratopia ("horned faces")[note 1] is a group of herbivorous, beaked dinosaurs which thrived in what are now North America and Asia, during the Cretaceous Period, although ancestral forms lived earlier, in the Jurassic. Early members such as Psittacosaurus were small and bipedal. Later members, including ceratopsids like Centrosaurus and Triceratops, became very large quadrupeds and developed elaborate facial horns and a neck frill. While the frill might have served to protect the vulnerable neck from predators, it may also have been used for display, thermoregulation, the attachment of large neck and chewing muscles or some combination of the above. Ceratopsians ranged in size from 1 meter (3 ft) and 23 kilograms (50 lb) to over 9 meters (30 ft) and 5,400 kg (12,000 lb).

Triceratops is by far the best-known ceratopsian to the general public. It is traditional for ceratopsian genus names to end in "-ceratops", although this is not always the case. One of the first named genera was Ceratops itself, which lent its name to the group, although it is considered a nomen dubium today as it has no distinguishing characteristics that are not also found in other ceratopsians.[1]

Anatomy[]

Centrosaurus, with large nasal horn, exaggerated epoccipitals, and bony processes over the front of the frill. Museum of Victoria.

Ceratopsians are easily recognized by features of the skull. On the tip of a ceratopsian upper jaw is the rostral bone, a unique bone found nowhere else in the animal kingdom. Along with the predentary bone, which forms the tip of the lower jaw in all ornithischians, the rostral forms a superficially parrot-like beak. Also, the jugal bones below the eye are very tall and flare out sideways, making the skull appear somewhat triangular when viewed from above. This triangular appearance is accentuated, in later ceratopsians, by the rearwards extension of the parietal and squamosal bones of the skull roof, to form the neck frill.[2][3]

Systematics[]

Ceratopsia was coined by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1890 to include dinosaurs possessing certain characteristic features, including horns, a rostral bone, teeth with two roots, fused neck vertebrae, and a forward-oriented pubis. Marsh considered the group distinct enough to warrant its own suborder within Ornithischia.[4]

As early as the 1960s, it was noted that the name Ceratopsia is actually incorrect linguistically and that it should be Ceratopia.[5] However, this spelling, while technically correct, has been used only rarely in the scientific literature, and the vast majority of paleontologists continue to use Ceratopsia. As the ICZN does not govern taxa above the level of superfamily, this is unlikely to change.

Taxonomy[]

An early ceratopsian: Psittacosaurus

Leptoceratops, a leptoceratopsid

A typical protoceratopsid: Protoceratops skeleton at the Wyoming Dinosaur Center

Styracosaurus, a centrosaurine ceratopsid

Following Marsh, Ceratopsia has usually been classified as a suborder within the order Ornithischia, though occasionally it has been reduced to the level of infraorder.[6]

Following is a list of ceratopsian genera by classification and location:

- Infraorder Ceratopsia

- Yinlong - (Xinjiang, western China)

- Family Chaoyangsauridae

- Xuanhuaceratops - (Hebei, China)

- Chaoyangsaurus - (Liaoning, northeastern China)

- Family Psittacosauridae

- Psittacosaurus - (China & Mongolia)

- Hongshanosaurus - (Liaoning, northeastern China)

- Clade Neoceratopsia

- Yamaceratops - (Mongolia)

- Auroraceratops - (Gansu, northwestern China)

- Family Archaeoceratopsidae

- Archaeoceratops - (Gansu, northwestern China)

- Liaoceratops - (Liaoning, northeastern China)

- Family Bagaceratopsidae

- Bagaceratops - (Mongolia)

- Gobiceratops - (Mongolia)

- Family Leptoceratopsidae

- Bainoceratops - (Mongolia)

- Cerasinops - (Montana, USA)

- Leptoceratops - (Alberta, Canada & Wyoming, USA)

- Montanoceratops - (Montana, USA)

- Prenoceratops - (Montana, USA)

- Udanoceratops - (Mongolia)

- Family Protoceratopsidae

- Graciliceratops - (Mongolia)

- Bagaceratops - (Mongolia)

- Breviceratops - (Mongolia)

- Lamaceratops - (Mongolia)

- Magnirostris - (Inner Mongolia, China)

- Platyceratops - (Mongolia)

- Protoceratops - (Mongolia)

- Superfamily Ceratopsoidea

- Zuniceratops - (New Mexico, USA)

- Family Ceratopsidae

There are several fragmentary Asian forms which may or may not be valid: Asiaceratops, Kulceratops, Microceratus, and Turanoceratops. Possible ceratopsians from the Southern Hemisphere include the Australian Serendipaceratops, known from an ulna, and Notoceratops from Argentina is known from a single toothless jaw (which has been lost).[7]

Phylogeny[]

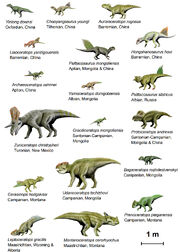

An illustration of 18 species of basal ceratopsia to scale

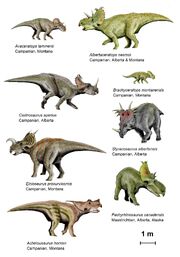

The centrosaurinae ceratopsians drawn to scale

Paleontologists today agree on the overall structure of the ceratopsian family tree, although there are differences on individual taxa. There have been several cladistic studies performed on basal ceratopsians since 2000. None have used every taxon listed above and many of the differences between the studies are still unresolved.

In clade-based phylogenetic taxonomy, Ceratopsia is often defined to include all marginocephalians more closely related to Triceratops than to Pachycephalosaurus.[8] Under this definition, the most basal known ceratopsians are Yinlong, from the Late Jurassic Period, along with Chaoyangsaurus and the family Psittacosauridae, from the Early Cretaceous Period, all of which were discovered in northern China or Mongolia. The rostral bone and flared jugals are already present in all of these forms, indicating that even earlier ceratopsians remain to be discovered.

The clade Neoceratopsia includes all ceratopsians more derived than psittacosaurids.[9][10] Another subset of neoceratopsians is called Coronosauria, which currently includes all ceratopsians more derived than Auroraceratops.[9] Coronosaurs show the first development of the neck frill and the fusion of the first several neck vertebrae to support the increasingly heavy head. Within Coronosauria, three groups are generally recognized, although the membership of these groups varies somewhat from study to study and some animals may not fit in any of them. One group can be called Protoceratopsidae and includes Protoceratops and its closest relatives, all Asian. Another group, Leptoceratopsidae, includes mostly North American animals that are more closely related to Leptoceratops. The Ceratopsoidea includes animals like Zuniceratops which are more closely related to the family Ceratopsidae. This last family includes Triceratops and all the large North American ceratopsians and is further divided into the subfamilies Centrosaurinae and Ceratopsinae (also known as Chasmosaurinae).

Xu/Makovicky/Chinnery Phylogeny[]

Xu Xing of the Chinese Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing, along with Peter Makovicky, formerly of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City and others, published a cladistic analysis in the 2002 description of Liaoceratops.[11] This analysis is very similar to one published by Makovicky in 2001.[12] Makovicky, who currently works at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, also included this analysis in his 2002 doctoral thesis. Xu and other colleagues added Yinlong to this analysis in 2006.[13]

Brenda Chinnery, formerly of the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana, independently described Prenoceratops in 2005 and published a new phylogeny.[14] In 2006, Makovicky and Mark Norell of the AMNH incorporated Chinnery's analysis into their own and also added Yamaceratops, although they were not able to include Yinlong.[15] The cladogram presented below is a combination of Xu, Makovicky, and their colleagues' most recent work.

Chaoyangsaurus is recovered in a more basal position than Psittacosauridae,[10] although Chinnery's original analysis finds it within Neoceratopsia. Protoceratopsidae is considered to be the sister group of Ceratopsoidea. The fragmentary Asiaceratops was included in these studies and is found to have a variable position, either as a basal neoceratopsian or as a leptoceratopsid, most likely due to the amount of missing information. Removal of Asiaceratops stabilizes the entire cladogram.

Makovicky's latest analysis includes IVPP V12722 ("Xuanhuasaurus"), a Late Jurassic ceratopsian from China that at the time was awaiting publication, but has since been published as Xuanhuaceratops. Kulceratops and Turanoceratops are considered nomina dubia in this study. Makovicky believes Lamaceratops, Magnirostris, and Platyceratops to be junior synonyms of Bagaceratops, and Bainoceratops to be synonymous with Protoceratops.

You/Dodson Phylogeny[]

You Hailu of Beijing's Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, was a co-author with Xu and Makovicky in 2002 but, in 2003, he and Peter Dodson from the University of Pennsylvania published a separate analysis.[16] The two presented this analysis again in 2004.[2] In 2005, You and three others, including Dodson, published on Auroraceratops and inserted this new dinosaur into their phylogeny.[17]

In contrast to the previous analysis, You and Dodson find Chaoyangsaurus to be the most basal neoceratopsian, more derived than Psittacosaurus,[10] while Leptoceratopsidae, not Protoceratopsidae, is recovered as the sister group of Ceratopsidae. This study includes Auroraceratops but lacks seven taxa found in Xu and Makovicky's work, so it is unclear how comparable the two studies are. Asiaceratops and Turanoceratops are each considered nomen dubium and not included. Along with Dong Zhiming, You described Magnirostris in 2003, but to date has not included it any of his cladograms.[18]

Paleobiology[]

Biogeography[]

Ceratopsian fossil discoveries. The presence of Jurassic ceratopsians only in Asia indicates an Asian origin for the group, while the more derived ceratopsids occur only in North America. Questionable remains are indicated with question marks.

Ceratopsia appears to have originated in Asia, as all of the earliest members are found there. Fragmentary remains, including teeth, which appear to be neoceratopsian, are found in North America from the Albian stage (112 to 100 million years ago), indicating that the group had dispersed across what is now the Bering Strait by the middle of the Cretaceous Period.[19] Almost all leptoceratopsids are North American, aside from Udanoceratops, which may represent a separate dispersal event, back into Asia. Ceratopsids and their immediate ancestors, such as Zuniceratops, are not found in Asia or any other continent and appear to be endemic to western North America.[2][14] However, if Notoceratops and Serendipaceratops are indeed ceratopsians, this hypothesis will be significantly affected.

Individual variation[]

Unlike almost all other dinosaur groups, skulls are the most commonly preserved elements of ceratopsian skeletons and many species are known only from skulls. There is a great deal of variation between and even within ceratopsian species. Complete growth series from embryo to adult are known for Psittacosaurus and Protoceratops, allowing the study of ontogenetic variation in these species.[20][21] Significant sexual dimorphism has been noted in Protoceratops and several ceratopsids.[2][3][22]

Ecological role[]

Psittacosaurus and Protoceratops are the most common dinosaurs in the different Mongolian sediments where they are found.[2]Triceratops fossils are far and away the most common dinosaur remains found in the latest Cretaceous rocks in the western United States, making up as much as 5/6ths of the large dinosaur fauna in some areas.[23] These facts indicate that some ceratopsians were the dominant herbivores in their environments.

Some species of ceratopsians, especially Centrosaurus and its relatives, appear to have been gregarious, living in herds. This is suggested by bonebed finds with the remains of many individuals of different ages.[3] Like modern migratory herds, they would have had a significant effect on their environment, as well as serving as a major food source for predators.

Diet[]

A highly debateable, although plausible, illustration of a Styracosaurus feeding on a small tyrannosaur carcass.

While percieved to be herbivores, there is evidence that at least some basal ceratopsians, such as Psittacosaurus were omnivores.[24][10] All ceratopsians had a large, deep and very often highly recurved beak, somewhat in the manner of a parrot. A beaked non-avian dinosaur is not unusual, but ceratopsian beaks are incredibly deep and robust compared to the flattened, spatulate bill of hadrosaurs or the slender croppers of other beaked dinosaurs. Furthermore, despite the immense side of their heads, ceratopsian bills are tapered, in that they bear little resemblance to the shovel-like mouths of ankylosaurs or hadrosaurs. Ceratopsian beaks seem to indicate that they were capable of producing a decent amount of bite force: certainly the degree of beak curvature produces greater mechanical advantage than a flattened or procumbent beak.[25]

Ceratopsians also posess a unique chewing system. Like other ornithopods, ceratopsians had replaceable, leaf-shaped teeth arranged in batteries. However, chewing ornithopods have pleurokinetic skulls – that is, the cheek region of the upper jaw can bulge ever so slightly when the lower jaw is adducted, meaning the food between their teeth is ground and torn laterally as they masticate. By contrast, ceratopsian jaws are not pleurokinetic and can only operate in the vertical plane. In fact, the tooth wear on ceratopsian teeth shows that the teeth occluded exactly in this manner. Because their cheek region is absolutely stuffed solid with teeth, their dentition essentially acts like a set of shears, chopping foodstuffs rather than grinding it.

The bone surface texture of ceratopsian frills doesn’t show features you’d expect from muscle anchorage and, besides, most of these frills have dirty-big holes in them: you can’t anchor big jaw adductor muscles to nothing but soft-tissue. However, this does not mean the real regions of jaw muscle attachment are anything to be sneezed at: rather, ceratopsians have large, robust coronoid processes (that is, an upright extension of bone on the lower jaw) that would allow for anchorage of big external adductor muscles. Conversely, the sites for anchoring the internal adductor musculature aren’t huge (except for in some basal forms), but the jaw joint certainly is: it’s like the sort of hinge you’d see on a drawbridge. Such a structure would not be needed if ceratopsians had weak, flimsy bites. Further physical breakdown of foodstuffs would take place in a stone-filled gizzard, as known in Psittacosaurus.

Based upon the nature of their jaws and beaks, it is determined that they were selective feeders: their beaks are far too narrow to harvest food en masse. From the large size of the gut cavities in these animals, it does appear that vegetative matter of some kind made up a reasonable percentage of their diet.

Posture and locomotion[]

Most restorations of ceratopsians show them with erect hindlimbs but semi-sprawling forelimbs, which suggest they were not fast movers. But Paul and Christiansen (2000) argued that at least the later ceratopsians had upright forelimbs and the larger species may have been as fast as rhinos, which can run at up to 56 km or 35 miles per hour.

See also[]

- Triceratops

- Marginocephalia

- Neoceratopsia

- Psittacosauridae

Notes[]

- ^ The term Ceratopsia ("horned faces") was originally coined by paleonologist O. C. Marsh in 1890.

References[]

- ^ Dodson, P. 1996. The Horned Dinosaurs. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 346pp.

- ^ a b c d e You H. & Dodson, P. 2004. Basal Ceratopsia. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 478-493.

- ^ a b c Dodson, P., Forster, C.A., & Sampson, S.D. 2004. Ceratopsidae. In: Dodson, P., Weishampel, D.B., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 494-513.

- ^ Marsh, O.C. (1890). "Additional characters of the Ceratopsidae, with notice of new Cretaceous dinosaurs." American Journal of Science, 39: 418-429.

- ^ Steel, R. 1969. Ornithischia. In: Kuhn, O. (Ed.). Handbuch de Paleoherpetologie (Part 15). Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag. 87pp.

- ^ Benton, M.J. (2004). 'Vertebrate Palaeontology, Third Edition. Blackwell Publishing, 472 pp.

- ^ Rich, T.H. & Vickers-Rich, P. 2003. Protoceratopsian? ulnae from the Early Cretaceous of Australia. Records of the Queen Victoria Museum. No. 113.

- ^ Sereno, P.C. 1998. A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with applications to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria. Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Palaontologie: Abhandlungen 210: 41-83.

- ^ a b Dodson, P., and Currie, P. . (1990). Neoceratopsia. In The Dinosauria (D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmolska, Eds.), pp. 593-618. Univ. of California Press, Berkeley.

- ^ a b c d Sereno, P. C. (1990). Psittacosauridae. In The Dinosauria (D. B. weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmolska, Eds.), pp. 579-592. Univ. of California Press, Berkeley.

- ^ Xu X., Makovicky, P.J., Wang X., Norell, M.A., You H. 2002. A ceratopsian dinosaur from China and the early evolution of Ceratopsia. Nature 416: 314-317.

- ^ Makovicky, P.J. 2001. A Montanoceratops cerorhynchus (Dinosauria: Ceratopsia) braincase from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, In: Tanke, D.H. & Carpenter, K. (Eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Pp. 243-262.

- ^ Xu X., Forster, C.A., Clark, J.M., & Mo J. 2006. A basal ceratopsian with transitional features from the Late Jurassic of northwestern China. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273: 2135-2140

- ^ a b Chinnery, B. 2005. Description of Prenoceratops pieganensis gen. et sp. nov. (Dinosauria: Neoceratopsia) from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24(3): 572–590.

- ^ Makovicky, P.J. & Norell, M.A. 2006. Yamaceratops dorngobiensis, a new primitive ceratopsian (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Cretaceous of Mongolia. American Museum Novitates 3530: 1-42.

- ^ You H. & Dodson, P. 2003. Redescription of neoceratopsian dinosaur Archaeoceratops and early evolution of Neoceratopsia. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 48(2): 261–272.

- ^ You H., Li D., Lamanna, M.C., & Dodson, P. 2005. On a new genus of basal neoceratopsian dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Gansu Province, China. Acta Geologica Sinica (English edition) 79(5): 593-597.

- ^ You H. & Dong Z. 2003. A new protoceratopsid (Dinosauria: Neoceratopsia) from the Late Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia, China. Acta Geologica Sinica (English edition). 77(3): 299-303.

- ^ Chinnery, B.J., Lipka, T.R., Kirkland, J.I., Parrish, J.M., & Brett-Surman, M.K. 1998. Neoceratopsian teeth from the Lower to Middle Cretaceous of North America. In: Lucas, S.G., Kirkland, J.I., & Estep, J.W. (Eds.). Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 14: 297-302.

- ^ Erickson, G.M. & Tumanova, T.A. 2000. Growth curve of Psittacosaurus mongoliensis Osborn (Ceratopsia: Psittacosauridae) inferred from long bone histology. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society of London 130: 551-566.

- ^ Dodson, P. 1976. Quantitative aspects of relative growth and sexual dimorphism in Protoceratops. Journal of Paleontology 50: 929-940.

- ^ Lehman, T.M. 1990. The ceratopsian subfamily Chasmosaurinae: sexual dimorphism and systematics. In: Carpenter, K. & Currie, P.J. (Eds.). Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 211-230.

- ^ Bakker, R.T. (1986). The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking The Mystery of the Dinosaurs and Their Extinction. William Morrow:New York, p. 438. ISBN 0140100555

- ^ Ostrom et al. (1990)

- ^ Bakker, R. T. (1978). Dinosaur feeding behavior and the origin of flowering plants. Nature 274, 661-663.

External links[]

- Introduction to the Ceratopsians, University of California Museum of Paleontology

- Marginocephalia at Palaeos.com (technical)

- Ceratopia, from Thescelosaurus! Web Site